Before Bruce Jeffreys and Jason McDermott worked on their first prototype for a new pair of spectacles, they knew little about eyewear—except that the high cost, poor quality and overwhelming choice made buying glasses a frustrating experience. Having previously co-founded car-sharing service GoGet, Bruce was determined to apply his entrepreneurial prowess to improve that experience. The result is Dresden, a radical new approach to making glasses with a social and environmental mission. In a conversation with Kai Brach, Editor at Today, Bruce Jeffreys explains how he’s taking on the fashion industry and why strong ethics is good for business.

In conversation

Bruce Jeffreys, Founder at Dresden

Kai Brach, Editor at Today

If you step into an eyewear store or optometrist you’re presented with a deluge of options by dozens of brands. What makes Dresden stand out in that crowded market?

Well, we started with a simple question: ‘What are all the things we don’t like about the glasses currently on offer?’ All the glasses we came across were too expensive, too fragile and there was also just too much choice, as you mentioned. And so the next question was: ‘How can we redesign such an established product from scratch and create a system that works for most people?’

And that’s the revolutionary idea right there: we came up with one shape for everybody. In the beginning, it sounded silly, because the fashion and advertising world keeps telling us that we’re all individuals and everyone needs something different. They continually emphasise our differences. What we learned through our prototyping, however, is that there is indeed a design that fits just about everybody. So we essentially approached selling glasses like selling t-shirts: a design that fits most people that you can get in a few different sizes. That’s it.

What also makes Dresden unique is its emphasis on having a social mission. Can you explain what that mission is?

Your eyesight affects every aspect of your life. It’s a fundamental human experience. If you’re not born with out-of-focus eyes, they’ll most likely lose focus as you age. This means your quality of life will diminish unless you’re getting your eyes checked and can afford a new pair of glasses regularly.

Let’s be honest, glasses are an industrially-made good that is fairly cheap to produce. We believe glasses are an essential product that should be accessible to everybody, not an expensive fashion item to be cherished. So our mission is to democratise this item—make it affordable—so that everybody can maintain their eyesight, be more independent, and engage fully with society.

As a proof-of-concept, you fitted a mobile optometry lab onto a trailer to deliver affordable prescription glasses to Australians on welfare living in rural areas. What did you take away from that experiment?

We were surprised about the amount of people that suffer from poor eyesight but are too afraid to get their eyes checked because they are worried about the cost involved. Most of these people are struggling with simple, everyday tasks—from reading the paper to finding directions. And we were only talking to low-income Australians; imagine how many people in developing countries are unable to participate in education, in work, and in their communities because of poor eyesight.

That experience really solidified our mission to turn glasses into a universally accessible thing, like clean water. Some studies I read say that by the year 2050 there’ll be more than five billion people worldwide who are unable to see clearly without glasses. Most of them won’t be able to afford $500 frames by some fancy fashion brand.

Besides the social impact, environmental considerations are also a big part of Dresden’s approach. How can glasses be made more sustainably?

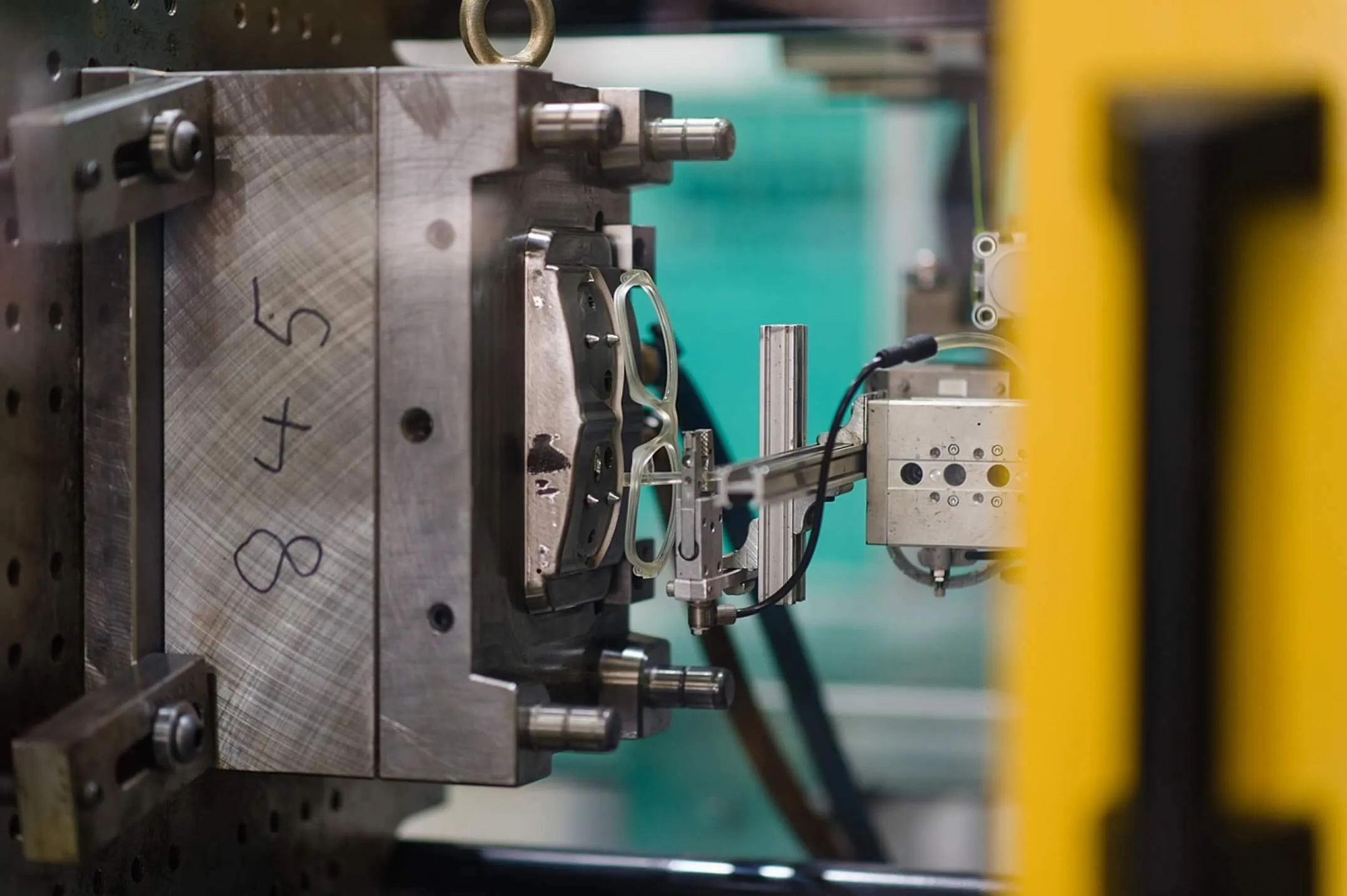

Using a more environmentally sustainable manufacturing process is an integral part of Dresden. Unlike the big established fashion brands, which outsource all of their manufacturing to China, our frames are made right here in Australia. This gives us a lot more control over the supply chain, labour and manufacturing practices.

Metal hinges are the most common breakage point in frames, so after a lot of trial and error, we came up with a better design that does away with metal entirely. Our frames are made from plastic only—we even replaced the metal screws with plastic pins. This has quite few environmental benefits. From a carbon footprint perspective, manufacturing a pair of Dresden has about 1% of the carbon footprint of regular frames. But using plastic only also means that our frames are completely recyclable at the end of their lifespan.

Of course, we are aware that plastic pollution is a huge issue and so we’ve developed a closed-loop, zero-waste approach where some of our frames are made from recycled materials such as milk bottle tops or old fishing nets. You can already buy these frames made from 100% recycled plastics in our shops, but our R&D is ongoing and we’re working with some research partners to fully close the loop. We won’t stop until all of our products are made from rubbish! Laughs

Given that recycling waste is literally piling up all over Australia right now, why is there so little innovation in this field?

Yeah, it’s a complex issue. In terms of manufacturing, you’re looking at a process that, over many decades, has been optimised around virgin materials. So if I put my economist hat on, I would say that the externalities do not allow for the added cost of recycled materials. In other words, it’s still not lucrative enough to reuse recycled materials because of the cost of collecting, sorting, and reprocessing them. In our current economic model, the environmental impact is still not priced into products, which is a real shame.

I think the main reason why Australia, in particular, is so far behind the rest of the developed world is that we’ve largely given up on our manufacturing industry and outsourced it to countries with cheaper labour and a more advanced supply chain infrastructure. That’s why every year it gets harder and harder to manufacture anything in Australia. The natural barriers—us being such a remote place—don’t help, of course. On the other hand, it creates new opportunities too: because we are so far away from other economies, you are kind of forced to innovate and ‘figure it out on our own’. I think Dresden is a good example of that.

Do you see being a ‘good actor’—having an ethical mindset—as a competitive advantage for a business?

I do. If what you do has a strong mission and sound values attached to it, it naturally attracts driven, committed people that want to make a contribution. People tend to be more engaged when there is another incentive at work than just money.

As a business, having that point of difference is really important too. It helps you to navigate the inevitable storms. If you are doing the same thing as your competitors, you are just another brand that is easily replaced. But if you’re going beyond just selling widgets and are driven by ambitious social or environmental goals, it provides a long-term vision that people gravitate towards.

If you are doing the same thing as your competitors, you are just another brand that is easily replaced. But if you’re going beyond just selling widgets and are driven by ambitious social or environmental goals, it provides a long-term vision that people gravitate towards.

Bruce Jeffreys

Tap to explore content

There is an increasing chorus of voices that questions the effectiveness of ‘conscious consumerism’, the idea that eco-driven brands can make consumerism sustainable. A good example is the switch to reusable canvas shopping bags: studies have shown that you’d have to use that canvas bag thousands of times to leave the same environmental footprint as a lightweight plastic bag. Is the eco-trend perhaps just a cop-out by brands so they can sell us more stuff without feeling bad about it?

Yes, but only if you believe that those brands can provide the solution to all of our environmental problems. Of course they can’t. What this conscious consumerism movement does is pose questions. It makes us aware of and talk about environmental issues.

To use the example of the shopping bag: the new awareness might be that plastic is bad and that we need to replace it with something that can be reused more often. So some people might bring along the bags they already have at home instead of buying new ones. Ironically, if you follow this through, you kind of end up where we started a few decades ago when we used wicker baskets and milk bottles. And I guess that’s the point.

So yeah, you can collapse into an existential crisis and point out that everything we do has an impact. But it’s also true that some things have a lesser impact and when we continue to ask hard questions we might get on a trajectory where that impact continues to decrease over time.

Do you see Dresden copy the ‘one-for-one’ model used by companies like TOMS Shoes and Warby Parker who donate a product to people in need for every product sold?

Absolutely not. In fact, I’m very sceptical of this kind of business model. While their initial intention was probably good, these models tend to engender poverty instead of lessen it. The idea that you help people long-term by giving them free stuff has largely been debunked. It just creates dependencies. Also, when you flood a local community with free products you are actually changing the economic dynamics of that market and potentially put local businesses out of work. They can’t compete with ‘free’.

So what we want to do at Dresden is actually develop a model that can work with and for those local communities in underdeveloped countries. Instead of selling over-priced glasses to rich people and giving away free ones to the poor, we want to offer affordable glasses to everyone—made, sold, and bought by locals.

When you bring an innovative new product to market, it can be challenging to educate new customers that what you are offering is superior to what’s already out there. How challenging is this education process and how do you go about it?

It’s a good question. Cutting through the noise is becoming harder and harder, especially when your product requires substantial behavioural change. That’s why GoGet took a relatively long time to take off.

At the time, car-sharing didn’t exist in Australia so we had to teach our customers a completely new model of transport that, in terms of how you use it, was somewhere between a taxi and a rental car. That’s obviously a lot more complicated to communicate than making people switch from Weetbix to Sultana Bran. Add to that that as a startup our marketing budget was pathetically tiny. Keep in mind that we were competing not just with classic car rental companies but also with new cars, full stop. Car brands like Toyota have a marketing budget that is in the hundreds of millions.

Dresden is a bit like GoGet in that we really want people to think differently about eyewear. It takes a while to get that message across but once you have some momentum, it’s really fascinating to see how that behavioural change affects people: it’s almost like you can’t ‘unsee’ it; you can’t go back to ‘the old way’. That’s when customers are eager to tell their friends about their new discovery. Your brand becomes this eye-opening experience for them. It’s invigorating when that happens.