There’s change brewing in the western deserts, and it’s been brewing for a long time. Martu people are amongst a small group of the Indigenous people who had no whitefella contact until the mid-60s. Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa is a Martu-led organisation delivering environmental, cultural and social programs to maintain Martu cultural identity and contribute to conservation projects of global significance.

Adam Morris, Chief Design Officer at Today sat down with Zan King, one of three General Managers at KJ (a Today client partner) to talk about the ways they’re using collaboration, co-design, and technology to nurture ancient stories, Indigenous culture and language, and to care for the land for all communities and future generations.

Could you give us a bit of an overview of Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa and the work you do?

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) is a Martu organisation. I think it is important to explain who the Martu are. Martu are an Indigenous group of people who lived a traditional lifestyle in the Western Desert until the 1940s, and for some, until the mid-1960s. The last Martu family group left the desert in about 1968. A majority of Martu were taken into missions. However, by the 1980s, Martu decided that they wanted to go back home—out to country. So, they returned to the desert and set up three Martu communities—Parnngurr, Punmu and Kunawarritji.

Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) began in 2005 by several Martu elders and whitefellas Sue Davenport and Peter Johnson. The first project for KJ was to record Martu stories and to repatriate old photos from the 40s, 50s, and 60s—bringing together documented Martu history. This information was brought together in a digital archive with the vision of keeping the information safe for future generations.

Alongside this work, a number of Martu talked about how they hadn’t been out to the remote country areas for a long time. As a result KJ started trips called kalyu ninti trips (or "knowledge of water holes"). These trips—or pilgrimages—involved small family groups going back out to visit country that they hadn’t been to for a long time. For some younger Martu it was their first time to country with their elders.

KJ started out quite small. Over the past 12 years, we’ve expanded to deliver an integrated suite of cultural, social and environmental programs. We employ over 370 Martu and 30 non-Martu staff. We’ve expanded quite rapidly! Despite this expansion, KJ started with a vision from the Martu elders, and it maintains that vision today—to keep culture strong and country healthy.

And of that group of 370-odd Martu that KJ employs, that’s mostly through the Ranger Program, right? Can you tell us some more about that?

Martu are the traditional owners of a large amount of country—13.5 million hectares which traverses part of three of Australia’s ten deserts. To put that in some perspective, we are talking about an area about two thirds the size of Victoria or twice the size of Tasmania.

This country is remote and its climate is harsh and unforgiving. "Deserts" often conjures up images of barren sand dunes but this is far from the case for Martu country, with surprising levels of vegetation, probably the largest wild population of bilbies in Australia, unique geckos and a range of other threatened or vulnerable species such as the Black-flanked Rock Wallaby.

To look after this country KJ started a ranger program in 2009 in one community. The concept of the program was discussed with some elders underneath a tree in Jigalong. We asked whether they would like to be rangers. They were horrified by the idea because they thought the job meant shooting dogs, that’s what they thought rangers were. We explained that the ranger program was a way to get people back out to country, to look after country, Pujiman way—or bushman way—together with western science. We started with a team of three old fellas and three young fellas in Jigalong and then from there we’ve expanded to run ranger teams in Jigalong, Punmu, Parnngurr and Kunawarritji.

The ranger teams work closely with the elders. The old people often tell us they want to go back to country, take their young people and teach them about their culture and country, and in doing so give them the information and authority to look after country both ways—Martu way, using traditional ecological knowledge, and whitefella way, using contemporary natural resource management practices. Activities in the ranger program include locating and cleaning waterholes, a fire program, and monitoring of threatened species such as the Greater Bilby, Black-flanked Rock Wallaby and Great Desert Skink. The rangers work in partnership with Parks and Wildlife as well as other scientists.

The rangers also work out on the Canning Stock Route, which is the iconic Australian 4WD track along culturally significant country. The rangers check permits, help tourists understand the country, and they often rescue a tourist or two that haven’t prepared properly!

When we last visited, one thing that really stuck out to me was how KJ empowers Martu to lead and drive your initiatives. The KJ board has an interesting structure, for example.

On the board, we have 12 Martu directors. There are two from each community and two from the diaspora. Each Martu board member serves for a two-year term. We have it structured so that the two people from the same community will serve one year together. This way before one person finishes, a new person starts; they dovetail into the position so that people are always passing on knowledge. We also have three non-voting advisory directors which are the two founders and one other person. The advisory directors provide financial and legal advice, but they can’t vote.

Surrounding the board are the senior cultural advisors. We have elders from all of the communities who attend our board meetings. They provide cultural advice and make sure that KJ is doing what Martu people want to do. We have several board meetings throughout the year and hold them in each of the communities. Our board meetings are open to all community members. People can come in and listen, understand what the organisation is doing, and can raise any concerns that they have.

Obviously, a board is a very western, mainstream construct, as is the concept of a company. There’s a lot of things Martu are having to navigate and understand about the mainstream world. To assist with this, we’ve developed a series of tools and techniques that help Martu to understand finances, governance, and how a company works.

It’s really interesting that contrast between traditional knowledge and learning about the new world. Could you tell us a little bit about how you support this two-way knowledge sharing? Like the Leadership Program, for example.

Through the Ranger Program, Martu started stepping up and taking on more responsibility. Many Martu showed an interest in wanting to understand more about this mainstream world. As a result, we started the Leadership Program. It’s similar to an adult education program. The topics the program covers include understanding corporate law, finances and governance structures. We do a lot of training on country and in communities. Participants in the leadership group also visit companies in Perth and over east, just like when they came to visit you at Today. It provides an opportunity for Martu to sit down with businesses and other boards and understand more about how the mainstream world works. It also provides an opportunity for the group to present on their program and develop confidence and public speaking skills.

After a few years Martu expressed their desire to understand how the criminal justice system works, so we’ve started navigating that space. We have hosted a number of senior police officers out on country. They come out on country for four or five days and they sit down and talk about the criminal justice system and have an opportunity to hear it from a Martu perspective. A lot of police officers walk away from the experience saying, “I wish I knew about this when I was a cadet. I wish I could have understood how kinship works before now.” It has helped police to understand kinship structures and how indigenous societies are formed. It completely changes the way they think about policing.

Together with the Pilbara Magistrate the leadership group have explored ideas like the Extraordinary License Program and restraining order cards. The extraordinary license program is a process where Martu can incrementally work towards obtaining a full license back over a five-year period.

With restraining orders, a number of Martu didn’t necessarily understand how to respect a restraining order and often found themselves breaching the order. The leadership group unpacked the complex issue and developed a card system to help Martu understand the different orders. The cards are being trialled by the Newman police.

The Leadership Program also visits people in the Roebourne Regional Prison. They hold sessions talking about new pathways - instead of cycling around in a destructive pattern. They talk about different choices people can make and the opportunities to get back out on country and into meaningful work when they leave prison. The Leadership Program has really grown from strength to strength.

Sadly we know that incarceration rates are disproportionately high for First Australians and reincarceration rates in WA are particularly bad. What role does reconnection to country have to play here?

Unfortunately, WA does have a high incarceration rate and people are still being sent to jail for things that they wouldn’t in the eastern states, like unpaid fines. We are hoping to see change in this space soon.

We believe with strong culture and language; you have a strong identity and pride. Being able to access country and engaging in meaningful work, you have much less chance of reoffending. We believe remote communities are important to invest in as it enables a continued connection to country and culture.

Martu communities are dry (alcohol-free zones), where Martu can engage in meaningful employment. Children can grow up in a safe, supportive family environment, where they will go to school because the curriculum and teaching environment resonates with their culture and their priorities. When we get people back on to country, they can reconnect with places that their grandparents used to walk. We find that when Martu are engaged in programs on country, they are less likely to travel to town and engage in anti-social behaviours.

As one Martu man said “We're hunter/gatherers by nature. Our mob have survived the desert for as long as we know, and they’ve done that within a social and cultural system of governance. When people go back on-country, people not only feel proud—“alright, I’m back on my country, this is my area, my family’s country”—but they feel a sense of ownership, leadership and responsibility; responsibility to family, responsibility to country and responsibility to society as a whole. They say, “I’m here, I know who I am and I know where I come from, and I’m going to take charge of my life,” and in doing so, they’re dealing with the dysfunctional aspects of their lives and their families’ lives out on-country—through a social, cultural and spiritual healing process.”

Through the leadership program we are working on a diversionary program concept. When people do end up going to court, we hope through the diversionary program, the magistrate has a choice. Instead of sending people straight to jail he/she can choose to offer them the chance to go back to country and work on the ranger team, or to get involved in the other KJ programs. We believe by giving the courts a choice, people will have a better chance to change. This program is in its infancy at the moment as we’re still looking for funding to expand the pilot concept.

It’s amazing that police officers are getting the opportunity to come out and stay on country and learn about community and culture. I wondered if it was having an impact on KJ being able to drive this diversion program? I imagine that if people are able to broaden their understanding, they can then see that there is another way.

Absolutely, we took the Pilbara magistrate out on country a number of years ago. Once he got out on country and saw how Martu operate on country, how strong they are on country and how much knowledge they have; it made him realise that there needs to be a different way. Similarly, having the police come out on country over the past three years has meant each of them go back home with more knowledge and a different perspective about Indigenous culture.

We are very lucky that we have a wonderful officer in charge in Newman. When he has new staff starting he sends them out on country with one of our teams. Recently two new officers went up to Kunawarritji and spent a week with the Kunawarritji rangers going out on country. It’s small steps, but every time a new police officer starts, they get to have some time out on country where Martu are strong, not just seeing people in town when they get in trouble.

We are also lucky enough to have the opportunity to visit new police recruits in Perth on occasion. The leadership team present about their program and provide some cultural awareness. Through this process Martu are trying to broaden the understanding of those involved in the criminal justice system; that there are two ways and two cultures alive here.

I think that many Indigenous groups across Australia are able to provide these opportunities. By doing so—and having conversations together—they can unpack differences and come to a greater understanding.

They say, “I’m here, I know who I am and I know where I come from, and I’m going to take charge of my life,” and in doing so, they’re dealing with the dysfunctional aspects of their lives and their families’ lives out on-country—through a social, cultural and spiritual healing process.

Martu man

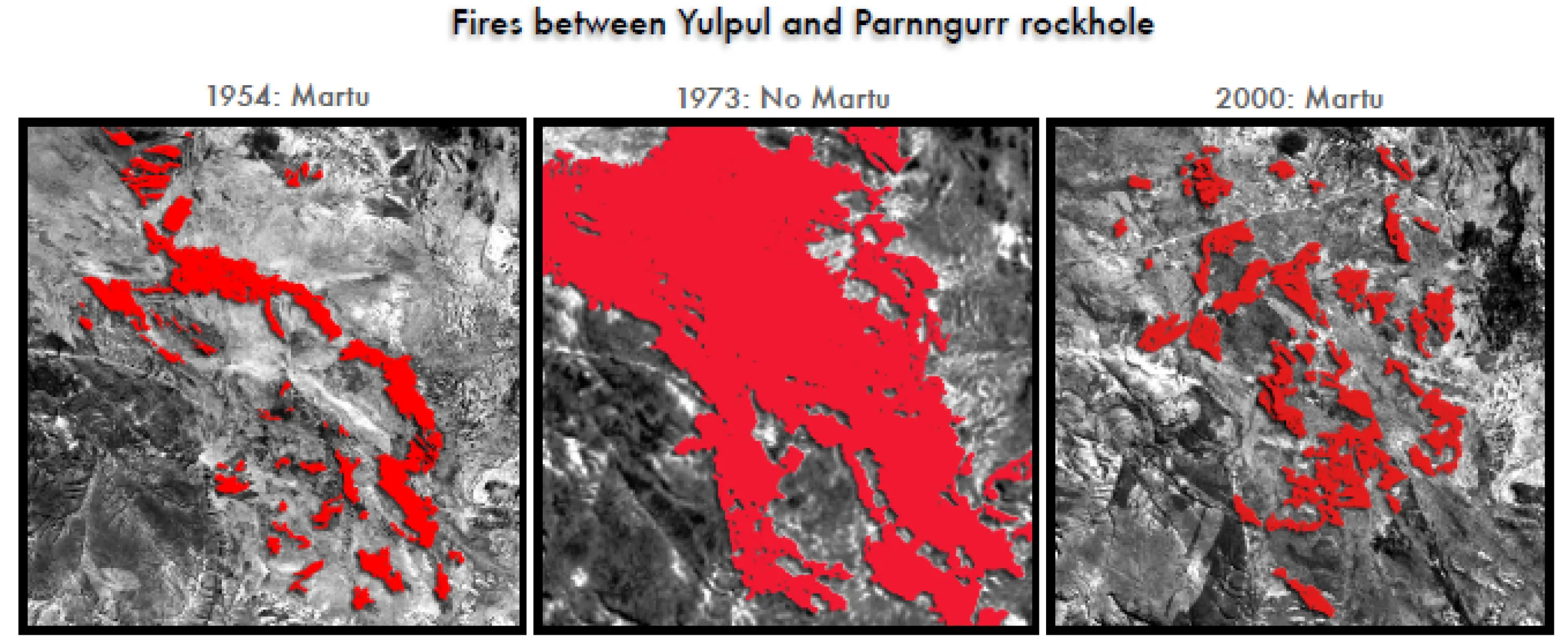

Let’s talk about land care for a moment. I remember out on country you showed us satellite images of pre-colonial spot fires and the contrast of large scale wildfires when Martu were taken away on to missions and couldn’t mosaic burn. That contrast was very powerful.

Martu have used fire for thousands of years for hunting, communication, encouraging the growth of bush foods and connecting with Jukurrpa (Dreaming). The resulting patchwork of fire scars and vegetation regrowth sustained both the biodiversity of the desert and the traditional Martu way of life.

When Martu left the desert in the 1960’s this small-scale burning ceased and large fuel loads occurred which resulted in mega-fires started by lightning. The positive interaction of Martu and fire with country can be seen through satellite imagery. There is satellite imagery pre-1960 which shows small patchwork mosaic patterns which occurred from Martu burning as they lived and walked on country. When Martu left the country in the late 1960s, there’s satellite imagery of country which shows large areas of burnt country. These fires were most likely hot wildfires which would have destroyed massive areas of country. When Martu went back out to country in the 80s, you can see on another satellite image small scale mosaic burning happening again which broke up the fuel loads and reduced the occurrence of large wildfires.

Martu rangers go out today and use both pujiman techniques of burning and western methods. Martu rangers often take the elders out with them to understand where to burn, how to burn, and how to read the wind and the country. The rangers also learn from Parks and Wildlife staff who have trained some rangers to be aerial incendiary operators. They go out with Parks and Wildlife to remote country and drop “little fire bombs” (not a scientific term) to burn the country—which helps reduce the chances of large wildfires. These small, cool burns protect cultural sites, threatened species habitats and communities. It’s a really wonderful synergy of using Martu knowledge and western technology to look after country.

Having to use helicopters like that really does paint an image of just how vast Martu country is. What role does that extreme distance play in your ability to share information and facilitate collaboration across communities?

Each community is very different, and the distances are great. Jigalong is a two-hour drive from Newman, and Kunawarritji is the furthest community which is around a nine-hour drive. Although the distances are great, we have several mechanisms in place to ensure we share information and collaborate across communities.

As KJ is a Martu company, its focus is on Martu futures, and therefore must always have strong mechanisms to hear the Martu voice. We have a model where there is a continuous cycle of planning, action and reviewing. An example of this is each year we visit each community to ask the community how things are going, what’s working and what they would like to see changes in. We take that feedback and incorporate it into our planning.

Alongside this process we have an AGM each year where lots of Martu who work with KJ come together. Often it is over 100 people coming together to celebrate the achievements of the year and to unpack what they want to do next. Martu drive the vision of the organisation so it is essential we have a constant checking in process to ensure the organisation is delivering what the people want.

The advancement of technology and satellite internet access means we have been able to use technology much more today than we have in the past. An example of this is every Monday morning we use an online conference facility to check in with everyone—which makes the distance seem much less. Martu have embraced technology and the ability to connect with staff and each other digitally.

That idea of reflection and sharing is interesting, what does that look like? How do you capture what’s shared and put it into action?

When checking in with communities we break out into lots of different groups—age groups, gender, kinships etc. We use a lot of visuals and participatory planning tools to discuss concepts and unpack ideas. Once we’ve completed the consultation, we pull all of the information together and produce a report, which is very visual. We then go back to communities to make sure we’ve recorded everything correctly.

Once our report is checked, staff complete a planning session to plan out the year’s annual work plan and incorporate what Martu want to do. Sometimes we can’t do everything in a year because our field seasons are short, but we are constantly trying to make sure we get to all the things that Martu want to do. This concept of checking in and planning occurs in all of our programs throughout the year.

That consultation process sounds familiar, like the way we’ve been working with KJ and Martu Rangers on the Stories of Country app. How do you see that contrast playing out, using innovation programs and reactivating that ancient knowledge?

The idea for the Stories of Country app came about over ten years ago. We were travelling on the Canning Stock Route with some elders when they met some tourists. They said to us, “They should really know the Martu story of this country.” We unpacked this concept a little more and realised there was a need for Martu to capture the stories of the elders and have them accessible for rangers to know and share on country. The desire to have knowledge accessible on country has intensified in recent years as Martu are acutely aware the old people are getting older and can’t get out to country as much as they used to. For Martu it’s a sense of security when you have your elders who know the country and can be with you out on a trip. On country they teach you the stories and knowledge they hold about the land and keep you culturally safe.

Martu therefore wanted to explore a way for elders to keep passing on knowledge to the younger generation even when they can’t get back out on to country anymore. With the advancement of technology in recent years KJ was ready to investigate the idea of developing an app. Through Department of Communication and Arts funding and the partnership with Today we were able to pilot the idea. Over the past twelve months KJ staff have been consulting with Martu and working out trial routes for the app. The elders and rangers work out what sites should be included, and with that site, what story, picture, film etc should accompany it. The idea is that when Martu are out country a GPS activated app will enable stories and visuals to be accessed near certain sites. All of the information is in Martu language. Next year we will begin looking to obtain further funding to expand the app and make it compatible with a range of devices. Once we pilot the app with some neighbouring groups, we hope to provide the software for other groups to personalise and use.

Martu are really open to exploring new ways of technology as long as it remains theirs and as long as they’re the main driver.

I think that’s the biggest thing. Martu drive technology, technology doesn’t drive Martu. It can easily become a whitefella way where Martu knowledge is being taken from them again, so we’re very conscious of making sure it’s Martu knowledge driving the process.

Martu are adaptive. If they can find a way of increasing their use of new technology, they will. They have taken to film and absolutely adore having a way of capturing stories for future generations.

An example of this is last week over 50 Martu were out on country participating in a language camp. During the camp they made a selection of short videos which explored different language concepts or words. These posts were made with the aim to publish them on Facebook.

Martu enjoy using Facebook and could see this as a mechanism for Martu who might not be living within the community anymore to access knowledge. It is also a way to help share Martu language with a broader non-Martu audience.

Martu want to capture as much knowledge and as many stories as they possibly can while the pujiman elders are still alive. It’s considered very important, so that their kids and the future generations will be able to access this information and be able to remain strong in culture and language. Clifton Girgiba, a middle-aged Martu man often reminds us “The old people told us to look after our culture, law and the land. We need to learn from the old people about the land, the names, their history, culture and language. We need to protect Martu culture, the land and the community that lives around it.” We hope the app is a way we can help Martu to achieve this.

I think that’s the biggest thing. Martu drive technology, technology doesn’t drive Martu. It can easily become a whitefella way where Martu knowledge is being taken from them again, so we’re very conscious of making sure it’s Martu knowledge driving the process.

Zan King

Throughout your time with KJ has there been a moment where you could really feel the momentum of positive change starting to take hold?

I’ve been with KJ over 10 years now and there have been several points along the way where the organisation and Martu have really started to embrace change which is positive for their community. I think the first moment was the start of the ranger program. Prior to this program there was very little meaningful employment in the community. From sitting under the tree with six fellas who thought rangers were people who came to shoot dogs through to the delivery of a ranger program across four communities, engaging hundreds of Martu in meaningful, engaging work is quite incredible. Through this program I have seen many Martu step up to be leaders within their team. It is wonderful that this program acknowledges and respects the knowledge Martu hold. Fundamentally they have university degrees in environmental science and this program enables them to utilise this knowledge as well as develop new skills in western natural resource management. I have loved watching both young Martu men and women develop confidence and pride through this program.

The development of the Leadership Program was another pivotal point for me. To watch Martu grow in confidence and want to know about the mainstream world has been fantastic. Instead of saying “yes” to whitefellas they know to ask questions and understand they have the right to be in control of their communities and their lives. Martu have developed a desire to understand the mainstream world so they can navigate it with confidence. I am so impressed when I see Martu stand and speak with confidence, particularly in conferences and with people in positions such as ministers in Canberra and Perth.

The range of impact that KJ has is so impressive in its impact and diversity—impact across culture, country, and social programs. What are some of the ways that you measure the impact you’re having?

Part of an action-reflection model is trying to measure the impact you have. We worked with Social Ventures Australia (SVA) in 2014 to undertake a social return on investment study. We wanted to understand how we could measure the impact we were having through our programs. SVA came up with a series of measurements for us and evaluated our programs. One of the biggest things that we found was that the programs KJ delivers have made transformational change throughout the communities. Overwhelmingly, the study showed Martu want to spend time on-country, caring for their country. Our programs enable Martu to fulfil their desire to live in Martu desert communities and to care for their country, rather than moving to town to live. Nearly every household in the desert communities is engaged in KJ work in one form or another.

The study showed that through our programs there has been an increase in traditional authority and pride, a reduction in incarceration rates, engagement in meaningful employment, and development of aspirations. Before KJ, kids didn’t know what they wanted to do when they grew up. Now they’re saying “I want to be a ranger when I grow up. I want to be a leader in my community.”

When the estimated social value that was generated was compared with the dollar investment, the social return of investment ratio equated to 3:1. This means for every $1 that was invested in the programs during the study period, approximately $3 of social value was created.

It was an important study to undertake. It assisted in showing that when evaluating programs, it is important to look at not only the economic return but the social and cultural outcomes that are a result of the programs being delivered.

Have any other organisations contacted KJ to learn from the successful programs you’ve been running?

We often get requests from other mobs to share our story. One example is our leadership program has been asked to provide governance training to other groups through the 10 Deserts Project. The 10 Deserts Project a fantastic project bringing all the desert communities together in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. The training sessions we have provided to date have been quite successful.

We often attend forums which bring together Indigenous groups to share our story and learn from others. One forum is through the Indigenous Desert Alliance (IDA). This IDA holds annual gatherings where over 200 indigenous people come together to share ideas. We’re often asked to present the way we’ve been working. Previously we’ve presented on the bilby monitoring methodology we developed with Dr Anya Skroblin, our leadership program and this year we hope to present on our language program. Lots of groups across Australia are doing amazing things, so it is fantastic to have an opportunity to meet and share ideas with each other.

It really is inspiring work, Zan. Any final thoughts you’d like to add?

I think Martu are an incredible group of people. They are so open and willing to share their culture and their knowledge with non-Martu people. They are incredibly warm and loving. I’ve had two kids during my time at KJ. They’ve both been given Martu names and are part of the community—what an extended family! I am very privileged and grateful to be able to work with such an amazing group of people and for such a fantastic organisation. I'm very lucky to be in the position that I am.

It’s been wonderful to have you share insights into the great work that KJ are doing to ensure a strong future for Australia’s most precious culture and country, it’s truly inspiring.

Thank you for the work you do with us. I am very excited to be working with Today on the Stories of Country app and appreciate the support you have provided us to date. Thanks!