2.2 billion people don’t have access to safe drinking water—about a third of the world’s population. Imagine if the solution to this crisis was powered by the sun, fit inside a suitcase, and was affordable to boot?

Jimi Peters from Oxfam Australia and Professor Xiwang Zhang from Monash University are working in a partnership to do just that. Kate Bensen, storyteller at Today, caught up with them to chat about how we might radically shift access to safe water for some of the world’s most remote and vulnerable communities.

In conversation

Jimi Peters, Oxfam Australia

Professor Xiwang Zhang, Monash University

Kate Bensen, Storyteller at Today

Jimi Peters, Oxfam Australia

Jimi can we start with an introduction of yourself and what your role is at Oxfam?

My name is Jimi Peters and I’m a proud Yorta Yorta man from the northern parts of Victoria and southern New South Wales, along the Murray River in Echuca.

I work in the First Peoples’ Program at Oxfam Australia as the National Programs Lead. We work alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their organisations to develop solutions and innovative answers to the issues that they believe are the most important. Oxfam has supported Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self-determination—individuals and communities—for about 40 years.

We work in the areas of advocacy and policy for practice and change; in political leadership through our women’s Straight Talk Program, and we partner with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to create the change they want to see. We are also exploring new initiatives in the land and water space to support community owned and driven campaigns and advocacy.

I work to look at what might be best for our mob on the ground and support our people to address issues they face on a daily basis, and to make sure they have a voice and are exercising their right to self determination.

I know you’ve had a long history in health, what were you doing before you came to Oxfam?

Before Oxfam, I worked in health for over 25 years. I worked at the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service in the early 90s and then I went to VACCHO (Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation), which is the State jurisdictional peak body for Aboriginal health. I was there for 19 years and I moved around the building in various roles, growing internally. I don’t have the formal qualifications that most people do; I’ve learnt mostly from going in and being a part of things, listening and observing. I was the Public Health Research Manager at VACCHO prior to leaving and I was the previous Chair for the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service and the Acting CEO at First Peoples Health and Wellbeing, which is a new Aboriginal Community Controlled health service that I helped establish.

I’ve had a long career in health. My father was one of the founders of Rumbalara Aboriginal Co-operative located in Shepparton in the 70s, so it was a given that I would end up in health, being his namesake.

Can you tell me about your shift from a health focus and how you made your way to Oxfam?

I think that the experience of working in Aboriginal Community Controlled services throughout my life has given me a deep understanding of the needs of the community. I’ve lived my life alongside my community, so I’ve shared a lot of experiences. I wanted to have a break last year, so I took four months off to reassess where my journey in life was heading and how I could contribute to community in a different way. At 48 years of age, I wanted to figure out what the next 20 years of my life were going to look like.

I’m really passionate about human rights. For me it’s never been just cultural elements that have driven me, it’s the fact that I believe everyone in the world should have equality and rights. I’ve been to places like South Africa and worked over there at the 5th International HIV and AIDs conference in 1999. That was a real eye-opener for me. It made me realise what services I had access to in Australia. I found myself in another country where people had endured similar types of trauma and disadvantage to First Peoples in Australia and didn’t have access to the services that we had, which made me realise how lucky I was.

I came back a different person. I realised that I had lived in a bubble for a long time and I wanted to pop the bubble and broaden the work I was doing to empower people on the ground at a grass-roots level. Coming to Oxfam was an opportunity for me to go to Aboriginal people directly and give them the self-determination to change their lives. I wanted to make sure that everyone who crossed my path, I could put a smile on their face or I could help them in some form. I’m that crazy person that will stop and talk to anyone on the street if they look sad.

Being an Aboriginal, gay man, I’ve faced discrimination and racism at levels that most people wouldn’t understand. Most people in the Aboriginal Community walk in two worlds, I have to walk in three. Being black and living in a white world was one I walked in, then being an Aboriginal gay man presented two other worlds I had to learn to walk in, and then there is the work side of things. When I first came into the workforce and was openly gay and proud of that, it was in the early 90s, it was really hard to get people to understand that I wasn’t really any different to them.

Those barriers and struggles have made me the person I am today. I am aware of the pain that came with navigating those different worlds and I never want to inflict that pain onto anyone else. I try to make people feel good about themselves and I try to draw out what they believe is good in their lives and own that. I think that’s important.

What are some of the changes that you and your community in Echuca have seen around water?

My first job at 16 was as an Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Officer on my traditional Yorta Yorta land. I worked in land and water and across cultural sites.

Working so closely with the land from a young age has meant watching the Murray deteriorate over the years. The area I grew up in was very green, there was a lot of fruit and orchards around and I don’t notice as many there anymore. The biggest thing I’ve noticed in my life is how water restrictions have become commonplace. However I have noticed that even when there are water restrictions and parts of the state are fighting for access to water, people in the city are still washing cars and hosing down their driveway. It feels like the connection isn’t made to the struggle others are facing.

Working in the land and water space has always been a passion of mine as well as my cultural right. I could see that we were experiencing something different from the stories that my grandparents had told me. My grandparents used to talk about fishing and how there were a lot of resources. I remember a story my great-grandmother told me one day, where the crayfish started to walk out of the river in front of her, which had never been seen before. When I heard those stories, it probably didn't click as I was still young, but when I got older and started working in cultural heritage, I realised that something must have been wrong with the water quality for that to happen. For my grandmother to say she could walk up to a riverbank and pick up a crayfish off the side, there was something going wrong there. I didn’t know much about climate change back then, but I knew something was wrong.

I’ve always been really passionate about wanting to make change happen. I started to learn about cattle farming and what that was doing to the areas around the river; when trees were pulled down and erosion became more damaging. The rivers were changing.

Traditional owners and farmers are watching precious water bypass their lands, on to cotton farmers for example. Other water management choices are doing irreversible damage to native flora like beautiful redgums, when stagnant water is left around their roots.

To me, the rivers are the veins of our land. Like us, if we have a blood clot we experience damage to our body. That’s what I feel like is happening to our rivers, they are clotting in areas and it’s only a matter of time before the heart stops. And we are the heart. If we don’t have access to water, what will we do?

I can see the changes happening in my life, and I can compare them to the stories from my grandparents and great-grandparents.

In the communities where Oxfam Australia and Monash University are looking to trial the prototype, what is access to water like currently?

I went along to a water rally up the Northern parts of Victoria on the Murray at the start of this year. It was a huge eye-opener for me. I went up there to listen to the community and people were telling me that they had travelled long distances to support other communities facing these issues. They were talking about the poor quality of water and this rally was their cry for help. They were saying that they can’t run air conditioners because the water smelled so bad, their kids have skin problems like dermatitis and eczema that they’ve never had before, they couldn’t do their washing or send their kids to school. People on dialysis machines were even affected because they couldn’t flush the machines with the polluted water. It really is a ripple effect which is having major impacts on Aboriginal people’s lives.

In communities in Northern NSW for example, communities face higher sodium content in their water than those in metropolitan areas. In some communities, if they drink 2.5L of water a day, they are consuming around ⅓ of the recommended daily amount of sodium from the water alone. This becomes an even greater health issue because people turn to sugary drinks for hydration when the water tastes bad. This has an effect on my community when we’re trying to address health concerns like diabetes with the older generations and dental problems within the younger population.

There are probably a lot of Australians who don’t know that problems like this exist here and assume that they only happen in developing countries.

In the city, because we have so much access to everything we need, we tend to operate on an out of mind, out of sight basis. If people can’t see it they often don’t believe it. It’s not until things like water restrictions and the increase in food prices come into practice that people start to pay a little bit more attention because it’s affecting them directly.

The further you go into rural areas, the less access to health services there are. A lot of communities we see have a fly-in-fly-out doctor service, they don’t have five major hospitals around the corner like we do in Melbourne. Someone from Mildura might have to travel six hours for a doctors appointment that will only last an hour; that’s two days out of their lives. When poor quality water starts impacting health, it becomes one challenge after another for people in rural areas. Not only do Aboriginal Communities face these issues, they’ve also faced the loss of their traditional cultural ways to hunt and fish as they did prior to colonisation.

To me, the rivers are the veins of our land. Like us, if we have a blood clot we experience damage to our body. That’s what I feel like is happening to our rivers, they are clotting in areas and it’s only a matter of time before the heart stops. And we are the heart. If we don’t have access to water, what will we do?

Jimi Peters

Tap to explore content

Professor Xiwang Zhang, Monash University

Professor Xiwang, how long you have been working on this prototype?

I’ve been working on this prototype for almost two years, but Oxfam Australia has had a partnership with Monash for 10 years.

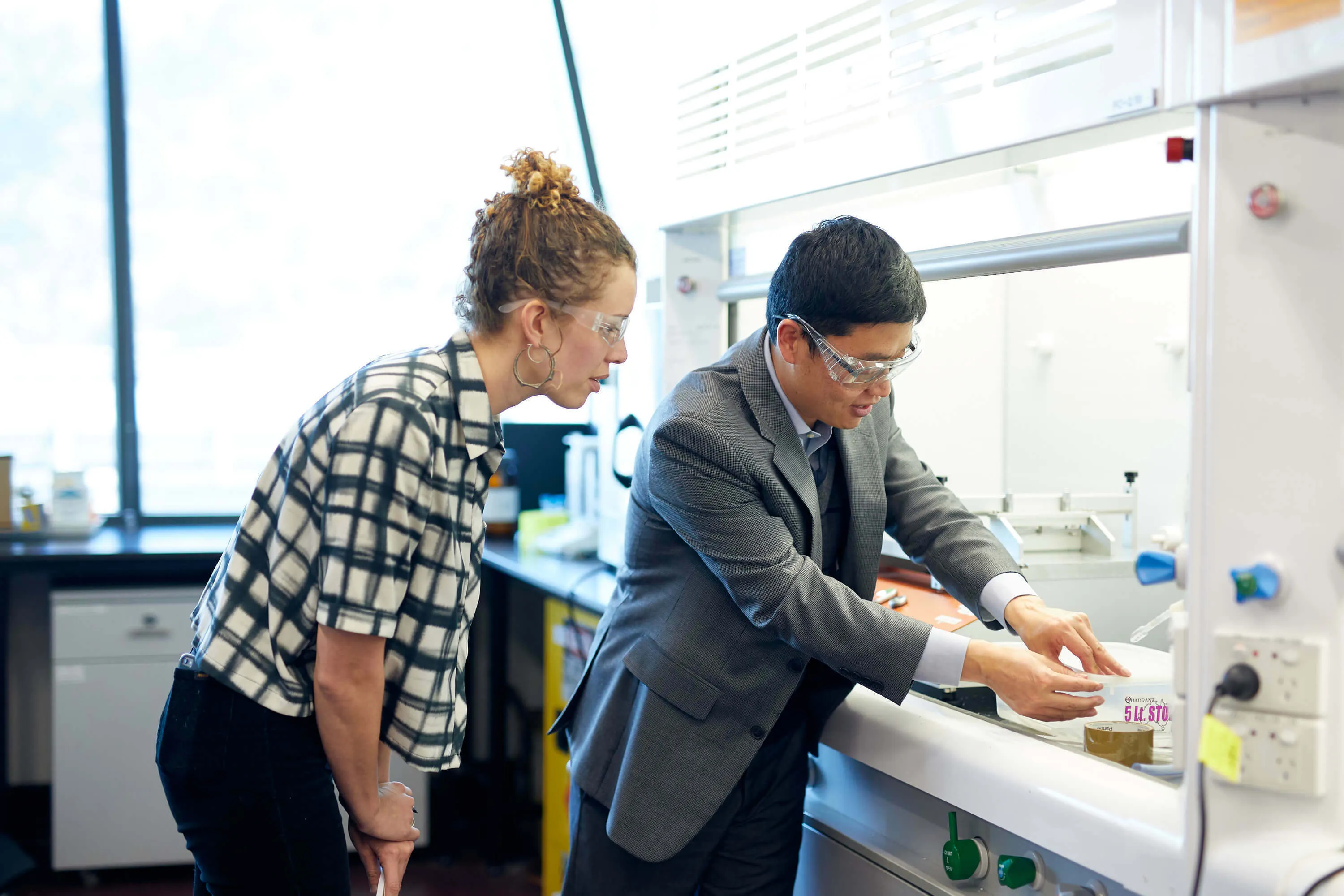

At the time Oxfam was doing a review of existing and emerging technologies in small-scale desalination and as a result, they wanted to know if it was possible to bring in an expert from Monash University that could help develop a prototype. They identified me as an option and then an initial discussion was held to see what the possibilities were.

Even now—we are in the 21st Century—and there are still billions of people who do not have access to clean water. It's very sad to hear this and it’s wonderful to be working on this critical issue.

I know that as a researcher you work in the lab to get some great ideas moving, which is fantastic. But how you can transfer your technology to help people—to change peoples lives—is very, very important. That's why today when Oxfam approached me, I said, “Yes, we would be so happy to work with you.”

Can you talk to us about how this technology works?

This technology is fully powered by solar energy. We are using affordable solar panels to generate electricity to run the pump. The pump will take water from a water source like a river, lake or ocean and move it through to the pre-filter. The pre-filter removes large suspended solids and large molecules. After that, only the soluble ions are left in the water. Then the water will go into the membrane module and in this membrane module—driven by the pressure provided by the pump—the water passes through the membrane and soluble ions are rejected. So that is essentially the whole process. We rely on the membrane to provide the clean water and at the same time pathogens, virus’ and bacteria are also efficiently removed. The water that comes from this module is clean and safe for drinking.

The ability to eliminate all bad bacteria from any water source is really powerful. How is this membrane different from other membranes?

Conventional membranes have to use very high pressure to run effectively, so what we are focussing on is the latest membrane that can be operated at low pressure. If you use high pressure, you consume more energy. Although membrane technology is more energy-efficient compared to conventional technology—like distillation—there is still a lot of room for improvement. That's why the focus of our hub is to develop better membranes and to keep making membrane technology more efficient.

In Melbourne and Sydney we have large seawater desalination plants, but let’s think about what larger-scale models actually need to operate. They need a high-pressure pump and they also use a lot of chemicals to clean the membrane after the system has run for a while. But when we think about regional and remote areas, they do not have access to grid electricity or chemicals. That's why we are using what we call innovative membrane technology. This technology can run at a low pressure, which makes it feasible to use a solar panel as the power supply. We have made this new design to make sure that the prototypes can run efficiently and go longer without chemical cleaning.

What is new for this prototype is that it’s small-scale, solar-driven, and it’s a compact design. If a device is half the size of a room, it becomes impossible to transport to remote areas. And because it would require high amounts of electricity, it would be very difficult to maintain and very expensive. This prototype will be very easy to take into the field in humanitarian emergencies or into remote areas. It’s incredibly accessible.

How many litres of water can the prototype clean per hour?

This will depend on the quality of the raw water. However, based on our calculations it can produce up to 1,000 litres per day. Which will roughly provide 10 families with water each day, assuming that it’s operating for six to eight hours.

If the source water is very, very poor quality and has a lot of suspended solids, or a lot of organic matter, that will compromise water filtration.

If the salinity of the water is between 1,000 and 5,000 parts per million (ppm), you can produce up to 1,000 litres in six to eight hours. For the regions we are targeting, the salinity of the water is around 2,000-3,000 ppm.

To try and protect the lifespan of the electric pump we have designed the device to produce enough water throughout the day so that it doesn’t have to run at night. The advantages of not including a big battery are that our device will be much lighter and the cost will be much lower. At this moment the cost is between $1,000 to $2,000.

The portable units that I’ve seen in action cost between $10,000 and $20,000, are much bigger than this prototype and run on fuel. So this is really incredible work!

Thank you. I think that is part of the challenge and why Oxfam came to me for this project. For people living in regional and remote areas, other units are far too expensive and no one can afford it. Sure, those units can produce good quality water, but it’s very expensive. My requirements were that it needed to be quite portable and also needed to be affordable.

It's a collaborative effort, but the idea is that Oxfam has expertise with community engagement and development that they can bring to the table and Monash has the research, engineering and technical skills. So it's a complimentary exploratory process.

How are you feeling about the prototype being tested in regional Aboriginal communities in Victoria?

I'm very excited about it. We will manufacture three to six prototypes and test it on different sites. The one we saw today, I call it the first generation. Currently, we are working on the second generation. It will be more robust and more efficient. So hopefully early next year we can share more progress with you.

It's my great pleasure to work with Oxfam. I am very interested in our knowledge and research helping people, particularly those in regional and remote areas who do not have access to clean water.

It's a feeling that is totally different from other academic achievements. I tell my team all the time—this is our priority and I need to make sure that everything can be delivered on time. It's a very exciting project.

Jimi Peters, Oxfam Australia

Jimi, what are the opportunities for Oxfam by being involved in this partnership with Monash University?

For me, it all links to closing the gap. I looked at it from an Aboriginal perspective. For us to successfully close the gap we have to have access to traditional lands, water, hunting and resources; things that we’ve had for over 65,000 years, which were literally taken off us during the colonisation of Australia. I started to realise that the reason we have so many problems with alcohol and substance abuse in some of our communities is that we’ve had all of our tradition taken away from us due to the Australian policies put in place since colonisation.

If supermarkets and small towns start closing because of this water crisis, food prices will inevitably go up as well and that brings even more challenges to rural Aboriginal Communities.

We should start asking ourselves what we can do to protect and rejuvenate wetland areas and land that we’ve had stolen from us; and how the government can learn from our traditional ways. For me as an Aboriginal person, it’s not just stolen generation, it’s stolen culture, stolen land and now stolen water.

I don’t want to set communities up to fail so I’m very passionate about empowering communities to take ownership over how this technology is implemented in their towns, and what kind of opportunities around employment and self determination there are for Aboriginal Communities facing these issues.

We should start asking ourselves what we can do to protect and rejuvenate wetland areas and land that we’ve had stolen from us; and how the government can learn from our traditional ways. For me as an Aboriginal person, it’s not just stolen generation, it’s stolen culture, stolen land and now stolen water.

Jimi Peters

Can you share some insights from the community and what their reaction was when you told them about the prototype?

They’re excited. I think they were a bit shocked that someone was listening to their challenges. They will always be sceptical, because I’m sure there’s been a lot of promises made that have never eventuated, especially around opportunity within these areas. They seem very keen to be part of something that can give them the basic right to water.

I truly believe that I’m here to support my community first and foremost, but something I’ve said all throughout this project is that it’s not just a black issue. I don’t want to go into a town and create divisions that may not already exist. So it’s important that we take the whole town on the journey however my role is to empower the Aboriginal Community within this process. We will work in partnership with the Aboriginal Community to choose some sites to put a desalination prototype into trial. We need to take the town on the journey so that my people are able to lead with pride, and we don’t create division within communities.

We want to start off in a very small community, where we know it will make a great impact. We are currently in discussion with traditional owners to explain fully what we want to trial and ask them what we need to do to make the process fully inclusive. Having water is a human right, it’s not just a black issue. We want to work together with communities to co-design the final technology—informed by community feedback generated during the trial.

We want to make sure that the quality of the water we provide to communities is perfect. The children growing up drinking this water are our future and we want to prevent future health issues within our communities. As part of my role as Oxfam’s First Peoples Programs Lead, we work to provide advocacy support to assist our communities in getting their message and stories out to the wider communities and Government. It’s really important that we get it right for our kids and include the younger generation in the journey because they are the ones that are going to inherit this.

I’m so impressed with the young ones today. I look at young people in my Aboriginal Community and think, “These are future leaders.” Not just within the Aboriginal Community, but within the climate change space for example. They’ve stood up and said, “We’re sick of you doing this to our future, and we’re not allowing you to do this to us anymore.” And rightfully so. They are more inspiring to me than I probably am to them, and that’s a good thing. I want to walk with them on this journey.

No matter what you believe your title is in this world, everyone should be made to feel included. Title to me is nothing. I might be a “National Programs Lead” here at Oxfam but I’m still Jimi the black man from Mooroopna who ran around with no shoes on. I think that we really need to walk side by side and leave no one behind.

Thanks so much for sharing with us, Jimi and Xiwang. It’s been a pleasure talking and learning from you both.

Having water is a human right, it’s not just a black issue. We want to work together with communities to co-design the final technology—informed by community feedback generated during the trial.

Jimi Peters