For many years I’ve described myself as a recovering academic. I completed my PhD many years ago, although left my fledgling academic career before too long. I realised I’d mostly be publishing in a highly specialised language, behind a paywall, and from the perspective of someone (me!) who had only interacted with the world as an object of study. I wanted to make an impact with my work, and to live and breathe the complexities that come with trying to achieve it.

I shifted into social research consulting, which led me into design consulting, and eventually to one of my big loves, service design. Now, from the vantage of someone who’s been working in industry for 15 years, I can see academic research and design practice moving towards an inflexion point, where new ‘translational design’ partnerships are resulting in distinctive impact opportunities, which neither academics nor designers could have achieved alone.

How does translational design work?

Over recent years, Today has been cultivating a translational design practice by working in partnership with academics to absorb their research, then translate it into programs, services and products that people can interact with. This translational practice is a common process in science, where it’s called ‘ translational research ’: think of researchers developing a new drug in a lab, then the rounds of testing and development before it lands on a shelf or can be prescribed as a part of clinical practice.

There has been a growing awareness of the value of translational design partnership as a way to unlock innovative, evidence-based research through design. It’s relatively new, as it’s taken specific conditions to get to this point. On one hand, design practice has been maturing: it’s more evidence-based, more aware of the need to design equitably and inclusively, and more cognisant of the systemic complexity it will impact. This maturation is reflected in practices like systemic design, strategic design and co-design. On the other hand, academic researchers are increasingly looking for ways to make an impact with their work. They also face pressure to demonstrate impact by solving real-world problems with the public funding they receive .

Today’s translational design practice has been evolving through a range of partnerships:

Burnet Institute

A repeatable, shareable process for distributing COVID safety content that multicultural communities can implement;

The VOICE platform (Victorian Ongoing Initiative for Community Engagement), that helps Burnet improve public health responses with multicultural communities; and

The Gist , a sex education program that we co-codesigned with young people to address online misinformation.

University of Western Australia

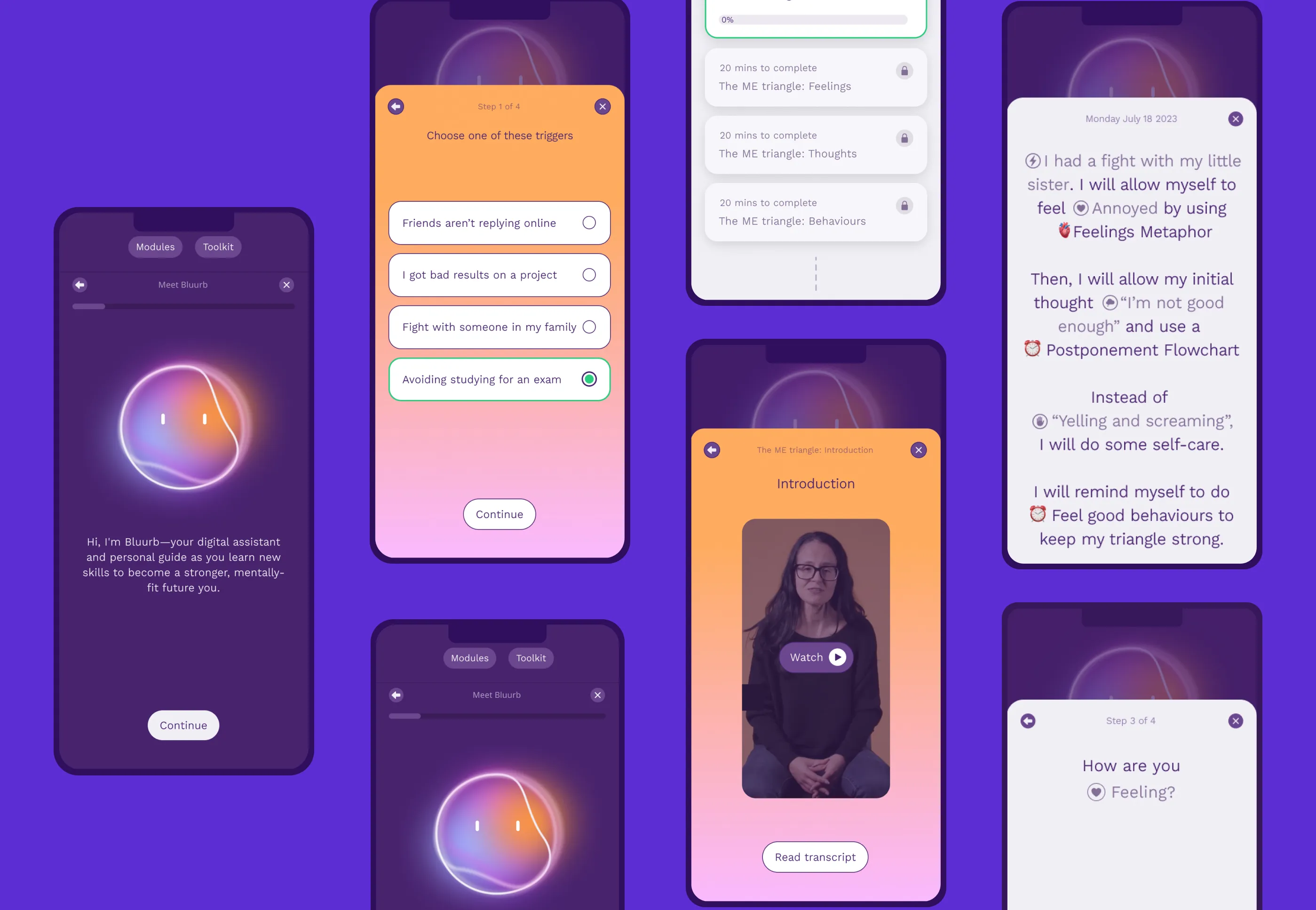

Partnering with clinical psychologists to co-create a product that helps young people develop preventative mental health skills .

Swinburne University

Co-creating social connection initiatives with communities living in Wyndham.

Whilst partnerships between academics and designers seem to make so much sense as a pathway to positive impact, they’re not an inherently easy fit. The pathway and resources to achieving this are also not always self-evident.

I wanted to understand more about what makes a productive and impactful partnership—one where research is accurately absorbed and the designed outputs produce their intended outcomes. So, I interviewed our client partners and designers from these projects to develop a set of pragmatic principles that could guide future translational design work.

Partnering with clinical psychologists and young peopleto co-create bluurb.me — a product that helps young people develop preventative mental health skills.

Which principles support effective translational design partnership?

If you’re an academic, researcher, designer or funder, and wondering how to make these partnerships work, here are five partnership principles that we consider in our own practice when collaborating with academic researchers.

1. Synchronise your speeds

Designers and academics work within vastly different organisational dynamics and operating models that impact how each slice and dice their time. And typically, neither has good insight into each other’s reality. Academics work around the semester calendar and long funding periods whilst designers typically speed through two-week sprint cycles and a quick cadence of project milestones. Deadlines do slide if these realities aren’t squared.

Compare calendars, align on project pace and your collaboration windows upfront to realistically determine what can be achieved together, and when.

The momentum was really quick... The academic world may or may not match up with that… Some times of year that would not be possible.

Lisa Saulsman, University of Western Australia

We want to move in a flurry of activity… it means we get to outputs. Beyond consultation, we’ll come back in two weeks and show you a prototype…

Sam Mackisack, Executive Director, Creative and Strategy, Today

2. Find common ways of working

There’s a very good chance that when academics and designers come together to partner, they’ll be arriving from different work cultures, rituals, and assumptions about roles and responsibilities. Academics are typically hired as experts, whereas designers expect to facilitate and decentralise their expertise (as is common in client services consultation). These things often feel innate, so in the context of a new collaboration, need to be made visible if to fashion a common working rhythm and shared culture.

Role titles often don’t reveal much at all, so when kicking off, lay out the value that each team member will bring by describing responsibilities, skills and abilities. Also explore how you might work in a blended team so that you can more easily immerse in each other’s worlds – and perhaps even rub off on each other in new, advantageous ways.

[What’s needed is] more embedding of researchers in design and designers in an organisation to really understand each other’s cultures better, and ways of working.

Megan Lim, Burnet Institute

What values are we contributing to the process? What do they have in terms of capability?

Dewani Shebubakar, Head of Strategy, Design and Innovation, Today

3. Align your rigours

Academics and designers share anxieties about methodological rigour when heading into an unknown partnership with each other.

Designers fear that academics will focus too much on minutiae, slow the design process down, and insist upon methodologies that aren’t suited for design research and testing, like randomised controlled trials.

Academics usually aren’t familiar with design research methods and the iterative design process. They fear that designers will fail to absorb the significance of their data, gloss over the details, and disappear into a black box that uncouples the evidence base from design decisions.

Methodological rigour in design and academia will look and feel different, so talk about these differences and come to an agreement about what a robust approach will need to encompass.

We’re talking in the same terminology but meaning different things. Rigour looks different, there needs to be socialisation on both sides when we talk about things.

Lisa Saulsman, University of Western Australia

Being contextually savvy is incredibly relevant in the design space… [I had a] concern that people would come in with fancy-dancy methods that are not contextually relevant and get some output that’s not useful.

Jane Farmer, Swinburne University

4. Define value beyond outputs

As designers, our contracts will (unsurprisingly) specify a designed output as a key deliverable. However in practice, the measures of a well-designed output can be traced through the strength of project stakeholder partnerships, a mature community engagement practice centred around safety and inclusion, and working with systemic literacy. The design process produces value that may result in outcomes that are well worth cultivating and exploring together, such as new partnerships, advocacy for community viewpoints, capability building (as stakeholders become exposed to the design process), and new, unforeseen project opportunities.

Whilst designers know that the practice encompasses more than artefact creation, this won’t be self-evident. Together, demystify design to expose the secondary opportunities for making impact.

...From the outside, it looks similar. Why are we paying someone so much money to do qual[itative research] for us? After we’d done it I saw the value – different ways of thinking, what the designers brought… Different outputs, different results than we would have got. Different ways of getting information out of participants and turning it into something in ways we wouldn’t have done.

Megan Lim, Burnet Institute

The best thing about the co-design process was building relationships with partners. [It] helped partners understand what the project was about.

Jane Farmer, Swinburne University

5. Educate for funding

Human-centred design approaches are increasingly finding their way into funders’ proposal requests, particularly co-design. This all seems like great news, except that translational design projects seem to characteristically lack adequate funding for the design process. Funding needs to cover more than just designers’ time, particularly for social impact projects. Some project costs are actually fundamental to maintaining a standard of research ethics and inclusive design practice, such as appropriate payment for participants’ time, psychological support, translators, time to brief and debrief with participants, travel and daycare allowances for participants, and meeting in-person, rather than online (which is often more expensive). Furthermore, funded opportunities for translational design are still few and far between. Funder awareness and understanding of these partnerships has a way to go.

When proposing a translational research project to a funder, designers and academics should collaborate closely to scope activities and timing, and consider the principles outlined above. A proposal for work is also an opportunity to educate funders, so include language that accurately sets funder expectations about what can be achieved within a set budget, as well as how the integrity of the work is contingent upon an inclusive process, which has associated costs.

What I’ve seen is they have no idea how much working with designers costs… They include $5,000 for co-design. Academic funders have no idea how much it costs and can’t conceive of it, or how to value it.

Megan Lim, Burnet Institute

Funders need to realise how essential collaboration for impact is – but it comes at a cost. The more cost, the better product you do have.

Lisa Saulsman, University of Western Australia

How to make an impact beyond a publication date?

We’ve been genuinely excited by the translational projects we’ve completed to-date. Looking over our project history, they promise innovation through cross-sector partnership. They also afford our teams creative multidisciplinarity, where strategic designers collaborate closely with content, experience or digital designers and developers. Our practice sharpens with each project as we immerse in new research contexts, and, with our academic partners, explore how to make the most meaningful impact.

If you’re curious about translational design practice or even have a project in mind, find a potential partner and talk through the principles. Do you have a shared view of them? Can you collaborate to define a project approach and ways of working that reflect them? Do you have the resources you need to run an inclusive process?

And of course, our doors are always open, so just drop us a line if you’d like to explore an opportunity together.